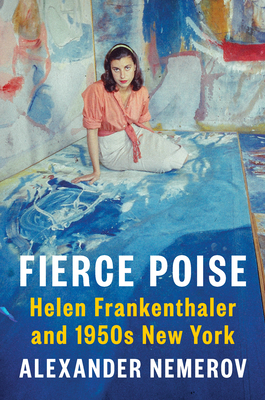

Book Review: Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York by Alexander Nemerov, published by Penguin Books, New York 2021. (4 out of 5 stars)

This is an interesting, ambitious and mostly well-written book, which focuses on artist Helen Frankenthaler’s early career in the 1950s, when she burst on the New York scene fresh out of Vermont’s Bennington College. She was noticed right away because, first, she had a strong pedigree of training as a painter; but more so because she was tall, good-looking, artistically confident and – as necessary – a skillful self-promoter.

The book made me like Frankenthaler and her work both more and less – the person more and some of the work a bit less.

Why do I like the person more? Because she was unapologetically all-in about her career, both in her dedication to her craft but also her enthusiasm and energy about self-promotion; all the while avoiding – unlike many male artists – unethical or self-destructive behavior. Granted, stories indicate that she may have been a bit full of herself and imperious at times (later in her career, even – gasp – culturally conservative??), but in the aggressive, profane, hard-drinking world of Abstract Expressionists – almost all male – a shrinking violet would never last.

Until reading this book, I didn’t know much about her personality and relationships but had a positive impression of her work in relation to other New York-based artists categorized as Abstract Expressionists. Her work is similarly large in scale but more varied, flowing and colorful than the typical jagged black-and-white-centric works of artists such as Robert Motherwell and Franz Kline.

In the past I have thought of her in somewhat stereotypical terms as bringing a softer, more visually appealing and “feminine” slant to mid-20th-century American art. But in reality, as an artist she had a strong personality, was typically very sure of how she wanted to proceed, and even her seemingly soft and flowing paintings such as the early “Mountains and Sea” can be seen as “explosive” or even violent in their markings, shapes and colors. Frankenthaler herself and this book’s author emphasize this explosiveness, although personally, I don’t see it quite that way. Nonetheless, her personality had a notable clarity and decisiveness. You can watch a YouTube of Frankenthaler appearing on “CBS Sunday Morning” in the mid-1980s, making decisions about where to hang paintings in the Andre Emmerich gallery, and see her no-nonsense decisiveness.

Though she was one of at least two Abstract Expressionists who came from wealthy backgrounds (her second husband Robert Motherwell was another), both she and Motherwell had to deal with significant challenges as children. Frankenthaler’s father, a prominent New York lawyer and judge, died when she was only eleven. Nemerov makes an interesting observation about this: it was soon after her father’s death that the young Helen became increasingly interested in painting; this interest may have been what led her out of her grief over her father’s death and into her life’s vocation.

Losing her father probably contributed to her rather steely determination and willingness to work hard and be aggressive when necessary to develop her career. Following an unconventional path for a daughter of New York City upper-crust Upper East Side wealth may have contributed as well. (Among other minor transgressions, she shocked her mother by moving to – Horrors! – the more middle-class and intellectual Upper West Side.)

Examples of her forceful, independent and decisive personality – which I find admirable! – are many:

The chalk line. A delightful example of the independent-minded, precocious artist is the story about the young Helen insisting on drawing a continuous chalk line on the sidewalk from the Metropolitan Museum to her family’s large apartment eight blocks away. Needless to say, it also points out the privileged upbringing she enjoyed.

Chatting up Clement Greenberg. Age 22 and just out of Bennington, she cold-called the leading commentator on modern art, Clement Greenberg – 20 years older – to encourage him to check out a gallery show she had curated on the work of recent Bennington grads. One source stated that she “met him at the show” but the reality is that she cold-called him. And there’s nothing wrong with that! In reality, the call led to a five-year relationship and important assistance in raising her visibility in the art community.

Rejecting a ‘woman painter’ identity. She made it abundantly clear that she was simply a painter, not automatically interested in “women’s subject matter” or identity at all. Following the lead of her teachers, she was keenly interested in the Western painting tradition, but scoffed at interviewers who asked why she didn’t explore or represent a “woman’s point of view”. It might have been advantageous from a promotion standpoint to highlight her gender, but this angle didn’t interest her.

Rejecting social / political messaging. Similar to the above, she rarely if ever included social or political commentary in her works. Often asked about this by interviewers, especially later in her career when social/political topics became more common – not to say ubiquitous – she vigorously defended her stance.

Being her own press agent. Frankenthaler may have made some phone calls and worked her network to convince the magazine Life to develop and publish an article about her and other artists in 1957, “Women Artists in Ascendance”, as well as articles in both Esquire and Playboy, then competing for the same wealthy-man-about-town advertising niche. Other artists grumbled about this and called her a self-promoter. One of them, the erudite and litigious Barnett Newman, happened to see a pre-print copy of the Esquire article and spotted himself in the background of one of the photos. He called her “cunning”, demanded that his image not be used anywhere in the article, and implied that he might initiate a lawsuit if the magazine included the image. But really, what’s wrong with encouraging publications to write about your work? Admittedly, if she knew that other artists would appear in the accompanying photos, she should have ensured that it was done with their permission; but this seems a minor complaint. I just admired her determination to become known & successful by hook or by crook.

No fists and no cursing. The Abstract Expressionists liked to congregate at the Cedar Bar, including women such as Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, Grace Hartigan, Lee Krasner (Pollock’s wife) and Joan Mitchell. It would have been convenient to do their best to fit in with the hard-drinking male crowd of artists, exchanging “ribald stories and groggy hugs”. In fact, Hartigan, who was from lower-middle-class New Jersey, apparently punched a poet, according to one story. Mitchell, who like Frankenthaler came from wealth, “behaved more like a brawler” and liberally sprinkled her conversation with the f-word. Not surprisingly, Frankenthaler didn’t change her style: “her style was different, a mix of uptown and Greenwich Village bohemianism, with no fists and no cursing”. As the author observes, her way of being “elegant and pretty and smart” was not a likely way to be taken seriously – or even accepted at all – among the hard-drinking Abstract Expressionists, but to her credit she didn’t change her style even to fit in among big-name, more famous artists.

Quality Control. Long after the decade that is this book’s focus, Frankenthaler served on the Advisory Council of the National Endowment for the Arts during the controversy over an exhibit that included the works of popular but controversial artists Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano. Several of Mapplethorpe’s photos were sexually explicit and one of Serrano’s photographs was “Piss Christ”, depicting a plastic crucifix in a tank of the artist’s urine. There were protests claiming that the art was obscene and, on the other side, that it would be reprehensible censorship if the works were excluded. US Senator Jess Helms railed against the artists. Frankenthaler didn’t think much of them either, but her distaste was simply that they weren’t good enough artists. With her typical independence and unconcerned about any consequences, she drily suggested that the NEA should practice more “quality control” in its selections.

== = = = = = =

She didn’t always get along with Hartigan and Mitchell. Not one to mince words, at one point Mitchell said she “despised” Frankenthaler and dismissed the latter’s stained canvas pictures as the work of “that Kotex painter”. Hartigan was much more of a friend, but seemed to consider some of Frankenthaler’s paintings dashed off and lacking in urgency: she once said that her friend’s paintings could have been painted “between cocktails and dinner”. Ouch! That’s what you call a frenemy!

As I mentioned, the book made me like Frankenthaler’s pictures less. More specifically, it made me like her early pictures less, which also happen to be the more famous ones. In fact, I see what Hartigan meant with her painfully clever remark.

For example, one of Frankenthaler’s most famous pictures, the much-praised “Mountains and Sea” which can be seen at the National Gallery in Washington, seems to me lacking in both urgency and – more important – paint.

The painting is famous because in it Frankenthaler applied an idea from Pollock in a much more intense and (as it turned out) influential way. Typically Pollock prepped his canvases with layer(s) of Dutch Boy lead white mixed with glue. But on this canvas Pollock applied black to a raw canvas and allowed it to spread and “stain” the canvas. Frankenthaler loved this effect. She went back to her studio and for the first time, worked on a canvas while it was on the floor, Pollock-style. She applied multiple turpentine-diluted colors to the raw canvas and let the colors spread naturally. The result was “Mountains and Sea”. Greenberg was very impressed by the painting and showed it to Washington DC artists Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland, who were equally impressed. Louis and Noland proceeded to develop this approach extensively and the method became known as Color Field Painting or Post-Painterly Abstraction. (“painterly” meaning showing evidence of brush strokes, palette knife and so on)

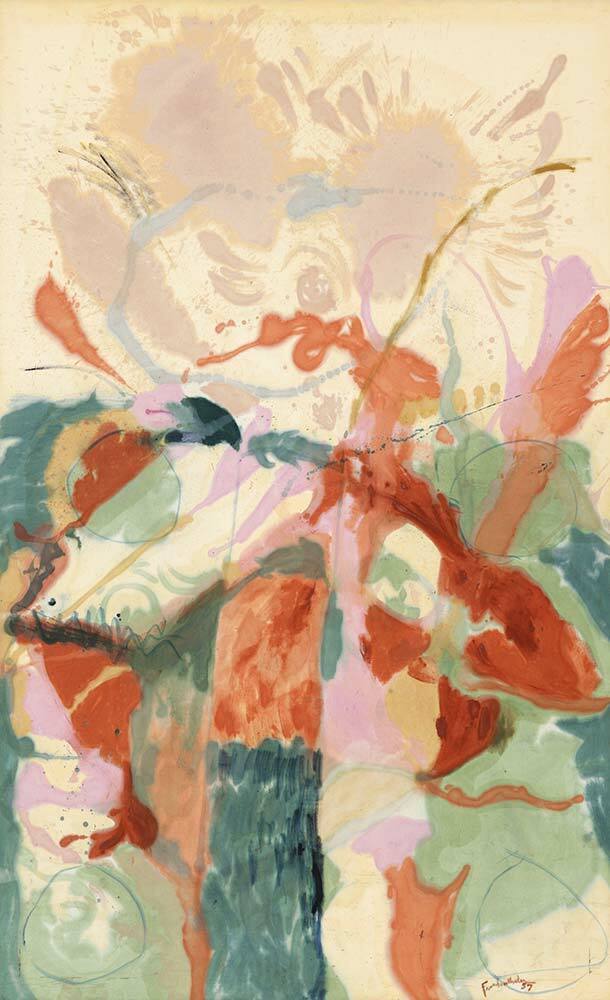

Personally, I don’t much care for “Mountains and Sea” (shown below). It strikes me as bland, boring and unfinished. The colors are weak pastels. It seems to be a timid attempt to turn a bouquet of flowers into a powerful abstract picture. Some other early Frankenthaler pictures strike me the same way, for example “Eden”, “Jacob’s Ladder” (shown below) and “Hotel Cro-Magnon”.

Mountains and Sea:

Jacob’s Ladder:

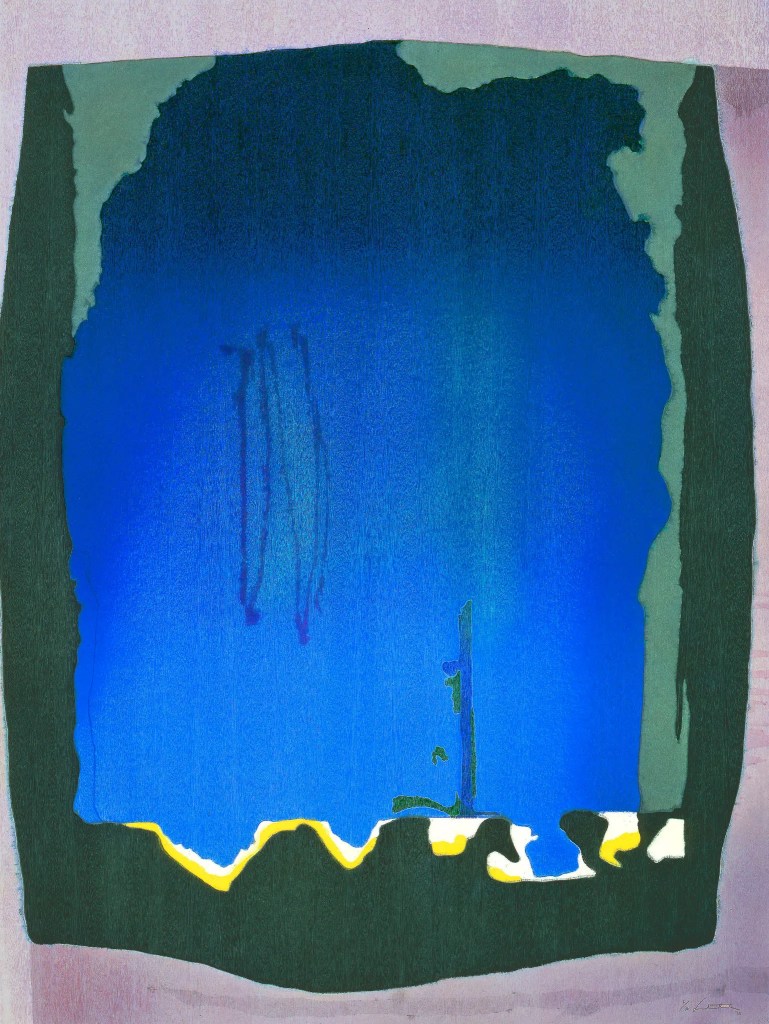

When it comes to abstraction, I tend to like pictures that are overflowing with color from edge to edge. That’s just me I guess. But Frankenthaler herself seemed to more frequently fill her pictures with color as her career progressed into the later 50s and beyond. (It’s possible that switching from oils to acrylics – not mentioned by the author but by one reviewer of the book – had an effect on this.) Inspiring and beautiful examples include “Acres” (1959, shown below), “Genuine Blue” (1970, shown below), “Sesame” (a serigraph print, 1970), “Royal Fireworks” (1975), “Circe” (1974) and “Freefall” (woodcut, 1992, shown below). I will happily gaze at these later pictures and categorize the earlier, less satisfying ones as juvenilia.

Acres:

Genuine Blue:

Freefall:

Another aspect of Frankenthaler’s early work I don’t care for relates to her pictures’ titles. According to the author, she would start a work with no idea of what she wanted to do or achieve, just improvise as she went, and then come up with a title afterwards. To me, this approach seems lame and is probably one of the reasons why many pictures by many artists are boringly called “Untitled”. I guess I prefer a bit more intentionality, or even ideas, from artists. Julie Mehretu, for example, is an abstract artist but she also incorporates complex ideas such as the history of Istanbul in her art.

I’m not sure if Frankenthaler continued with this approach throughout her career and I’d be curious to find out.

Although I really like this book and found it both entertaining and educational, I didn’t care for one habit of the author. This is his tendency to provide highly poetic, effusive and eyebrow-raising descriptions of the art. Here’s an example:

Something in her pictures implies that color is a force, as if the painter must commit to it as a full-on saturation of the canvas, a power that all but dyes itself on the eye, if it is to have any reason for being there at all. The blazing yellow and aquamarine of “Acres”, another painting of 1959, not to mention its royal blue and red, explode upon the viewer as if the artist were not only committed to their intrinsic beauties but feared that anything less than such a deep-dyed commitment would allow an unspecified but horrible night to return.

“Acres” is certainly a beautiful and intense picture, but to me the above description is a bit over the top. However, “your mileage may vary” and certainly some readers may find such descriptions very powerful.

There are other interesting aspects of this book I’d like to explore, for example the idea that Frankenthaler’s art is particularly Jewish (brought up in Chapter 11), but I’ve gone on much longer than my typical book review so I’ll pass up that temptation.

To return to my theme, this (partial) biography made me like Helen Frankenthaler and her work both more and less – the person more and some of the work a bit less. On the latter point though, certainly I found some of her early works bland, lame & lackluster; but the later, more colorful and intense pictures and prints she produced from 1959 to the end of her career more than make up for my lack of enthusiasm for her earliest works, and she remains one of my all-time favorite artists.

Leave a comment