Venice – the one in Italy – alternates two huge fairs, the Architecture Biennale and the Art Biennale, in a tradition that dates all the way back to 1893, when it marked the 25th anniversary of the marriage of King Umberto I of Italy to Margherita of Savoy.

In April my wife and I were fortunate to attend the current edition of the Biennale art fair, which actually lasts until November. I found the fair to be an all around spectacular show. It seemed especially amazing and fresh – if also plenty weird in spots – because I had never heard of any of the artists before.

Of course there was some art that didn’t appeal to me, which I would place in two categories:

- works that didn’t speak to me or catch my interest, but which may have intrinsic value and may appeal to others, or..

- works that were just, in my opinion, plain bad and/or stupid (in their defense, sometimes entertainingly bad or stupid – LOL); but again, maybe I’m missing something – it’s a distinct possibility!

Naturally, just as with book reviews I’ve written on this blog, I focus on what’s interesting and worth attention, and don’t waste time on the bad or stupid stuff!

Accordingly, I want to highlight a LARGE group of art works that I really enjoyed and found interesting and meaningful. The group is large enough that I’m going to make two blog posts out of it, this being Part 1.

As part of choosing what to include, I had to ask myself the question “What makes me really enjoy an artwork and find it interesting and meaningful?”

I concluded that the art work needs to have some combination, as many as possible, of these characteristics:

- A high degree of skill/craft is evident

- Effort: the work seems to have required a large amount of dedication & effort

- Creativity: its technique, subject matter or approach (or a combo) is innovative

- Beauty (I’m especially susceptible to beautiful colors and color combinations, which is probably why I prefer paintings to sculpture or B&W photography)

- Wow factor: something amazing

- Content: the work is “about something” – it’s meaningful and/or educational in some way, e.g. it exposes me to startlingly new & interesting information or is at least thought-provoking

- Many details: especially if they are in layers or levels that you can discover as you look at and learn about the work; they could be layers of paint, layers of meaning, a dog or saint hiding in the corner of the picture, etc. (I mention a saint because after all, we were in Italy)

- Humor

- Emotional impact

I did a search to find out what the internet thinks about this – admittedly risky on any topic! – and found this interesting blog post that presents a similar set of characteristics.

So now, having put this list out there, I don’t plan to explain which of the characteristics were applicable for each art work I’m going to mention. (In some cases of course, I’m sure my enthusiasm will get the best of me.) But in every case I’ll include a photo and/or video so I’ll have a convenient record and you can take a look and decide for yourself.

How the Art Biennale is spread around Venice

Before diving in though, I need to outline how the Art Biennale is structured. The key thing you need to know is that most of the Biennale is housed on the east side of Venice in two large areas:

- The Giardini (gardens), a park-like area in the far southeast corner of the city containing a large central exhibition building (Central Pavilion) along with about 30 national pavilions – small freestanding buildings owned and operated by specific countries. Typical of Venice, a canal (“rio” as they’re called) bisects the Giardini. I was interested to see that the city of Venice itself has a pavilion among all the national pavilions – and it turned out to be one of my favorites.

- The Arsenale (arsenal), a larger area of 110 acres on the east side of the city adjoining the Giardini. The Arsenale was formerly the headquarters of the navy of the Venetian Republic, from its beginning in 1104 until its demise when Napoleon’s forces conquered Venice in 1797. The Arsenal was the site where Venetian navy ships were constructed and maintained. As a result, it contains several huge, cavernous, very old buildings that function well now as art exhibition spaces. Everyone knows that when it comes to famous people of history, Italians don’t fool around. So it should not be surprising to learn that none other than Galileo was a consultant to the Arsenale in the late 16th and 17th century, helping to research and solve problems in the areas of ballistics, production, logistics and materials science. Certainly he would be surprised to see how the Arsenale is being used now! Specifically, the Arsenale buildings are used for both a huge display of (mostly) contemporary art (the “International Exhibition”), and for about 20 national pavilions. A difference between the national pavilions in the Giardini and those in the Arsenale is that the pavilions are all separate, free-standing buildings in the Giardini (maybe reminiscent of a World’s Fair, but smaller-scale), while in the Arsenale they are sections or rooms in large buildings.

The Giardini and Arsenale alone are large enough to house a tremendous amount of art and exhaust the most energetic art lovers. Don’t try to do the whole Biennale in one day! In fact, I doubt if any visitor sees the entire Biennale even if they have a week – it’s that big.

But there’s a lot more beyond the Giardini and Arsenale. Venice has a lot of beautiful old atmospheric palaces (“palazzi”) and other spaces, including “deconsecrated” or no-longer-used churches, that are often underutilized and make perfect spaces for art. There are two categories of exhibits using these spaces:

- Official Biennale-branded exhibitions elsewhere in Venice. These come in two categories: 1) National pavilions – often smaller population countries like Kazakhstan, Cameroon and Panama, but also including Nigeria; and 2) Biennale-branded exhibitions not tied to a particular country. These “collateral” exhibitions may pop up anywhere in Venice as you walk around. What they have in common is branding/signage that shows they are officially associated with the Biennale.

- Independent exhibitions taking advantage of the large number of art lovers visiting Venice during the Art Biennale as well as, again, the plentiful supply of beautiful, high-ceilinged, atmospheric spaces perfect for exhibitions. These may be sponsored by commercial galleries or even world-famous museums such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).

This year’s Art Biennale Theme

Before getting into the artworks, I should mention the theme: this edition of the Biennale has the overall theme “Stranieri Ovunque”, Italian for “Foreigners Everywhere”. To me and plenty of other observers, this has a rather awkward sound, like the rant of a xenophobe or a Venetian complaining about tourists. It actually is a reference to a work of neon art by the Sicily-based collective “Claire Fontaine”, which is included in the Arsenale section of the Biennale. The phrase itself apparently is a reference to a work by a Turin-based art collective which was created in the early 2000s. All this is very confusing. I didn’t find the neon artwork very memorable, as it consisted of neon signs in many languages and typefaces expressing the concept “Foreigners Everywhere”. It was certainly unique.

However, the comments of the Biennale’s overall curator, Brazilian Adriano Pedrosa have been helpful. He links the phrase “foreigners everywhere” to a general feeling of foreign-ness that anyone can feel, depending on their situation. This article in the New York Times provided clarification:

The title is a provocation, weighted by the anti-immigrant agendas of Italy, Hungary and other countries in the last few years. Pedrosa, however, speaks about celebrating the foreigner and the historic waves of migration across the planet, offering a catalog of synonyms — “Immigrant, émigré, expatriate” — even as he expands the concept. “I take this image of the foreigner and unfold it into the queer, the outsider, the Indigenous,” he said.

I find this definition interesting and useful, and as such, despite its strangeness, I have to say I prefer “Foreigners Everywhere” to the bland, generic themes of the last two Art Biennales, which were “The Milk of Dreams” in 2022 and “May You Live in Interesting Times” in 2019.

OK, with the above categories, locations and theme in mind, here are the artworks that caught my eye!

(Note: I’ve included many hyperlinks that will take you to places where you can see more details, e.g. Biennale pages, Wikipedia articles, news media articles and so on. I hope you will check out some of them.)

Giardini – Central Pavilion

The large central pavilion contains a variety of exhibits curated by the overall curator Adriano Pedrosa. One emphasis was on artists who had never appeared in any previous Biennale, especially from the “Global South”, even if they were active decades ago. The best section contained portraits; below are some of my favorites.

Jamini Roy (Indian, 1887-1972), “Untitled” (Krishna with Parrot)

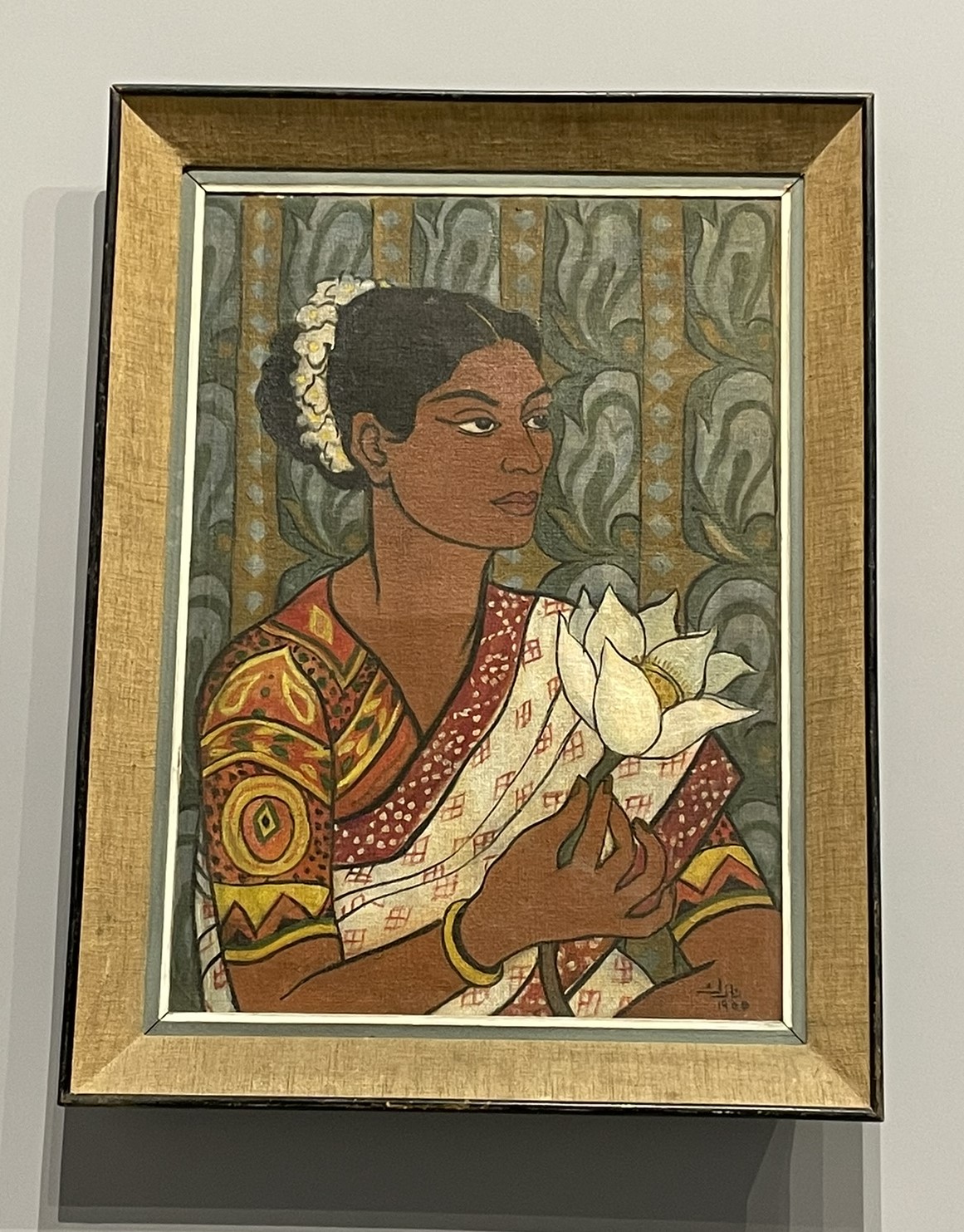

Nazek Hamdi (Egyptian, 1926-2019), The Lotus Girl (1955)

Tahia Halim (Egyptian, 1919-2003), Three Nubians

Jewad Selim, (Iraqi, 1919-1961), Woman and a Jug (1957)

Raquel Forner (Argentinian, 1902-1988), Self-Portrait (1941)

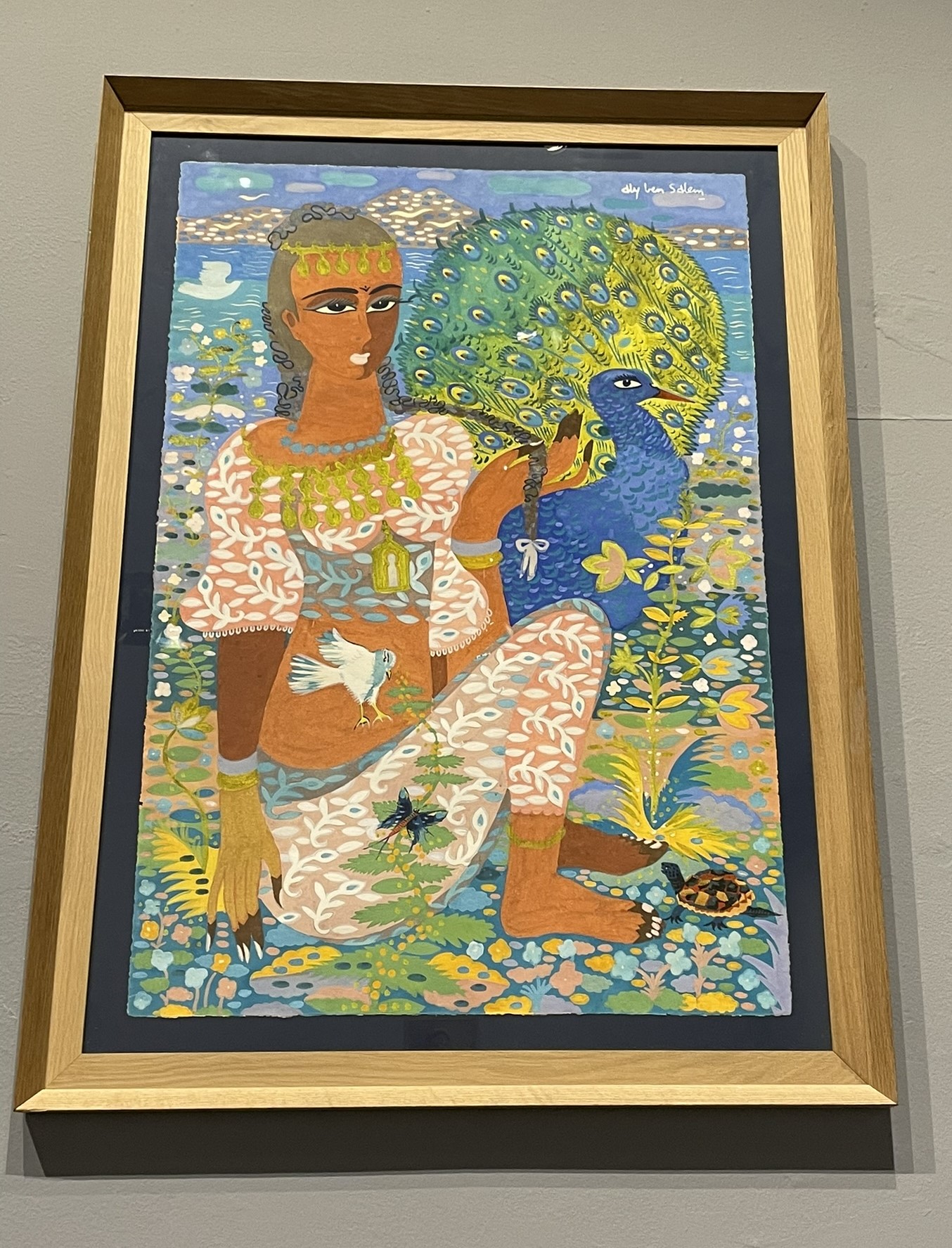

Aly Ben Salem (Tunisian, 1910-2001), Woman with Peacock (undated)

And so you can visualize it, here’s the entrance to the Central Pavilion in the Giardini, where all the above paintings can be seen. This amazing mural was created by MAHKU, a collective of indigenous artists in Brazil.

National Pavilions

I want to highlight four national pavilions: those of Canada, Australia, Benin and Nigeria. The Canadian and Australian pavilions are in the Giardini, where most of the national pavilions are located – between the Central Pavilion shown above and the water’s edge. The water is really a part of the Adriatic Sea, but it’s behind a long barrier island (the Lido) so it’s called the Venetian lagoon or laguna.

Before leaving the Giardini I’ll talk about a unique pavilion because it’s for the City of Venice. I guess the hosts should be allowed to be the only city that has its own pavilion!

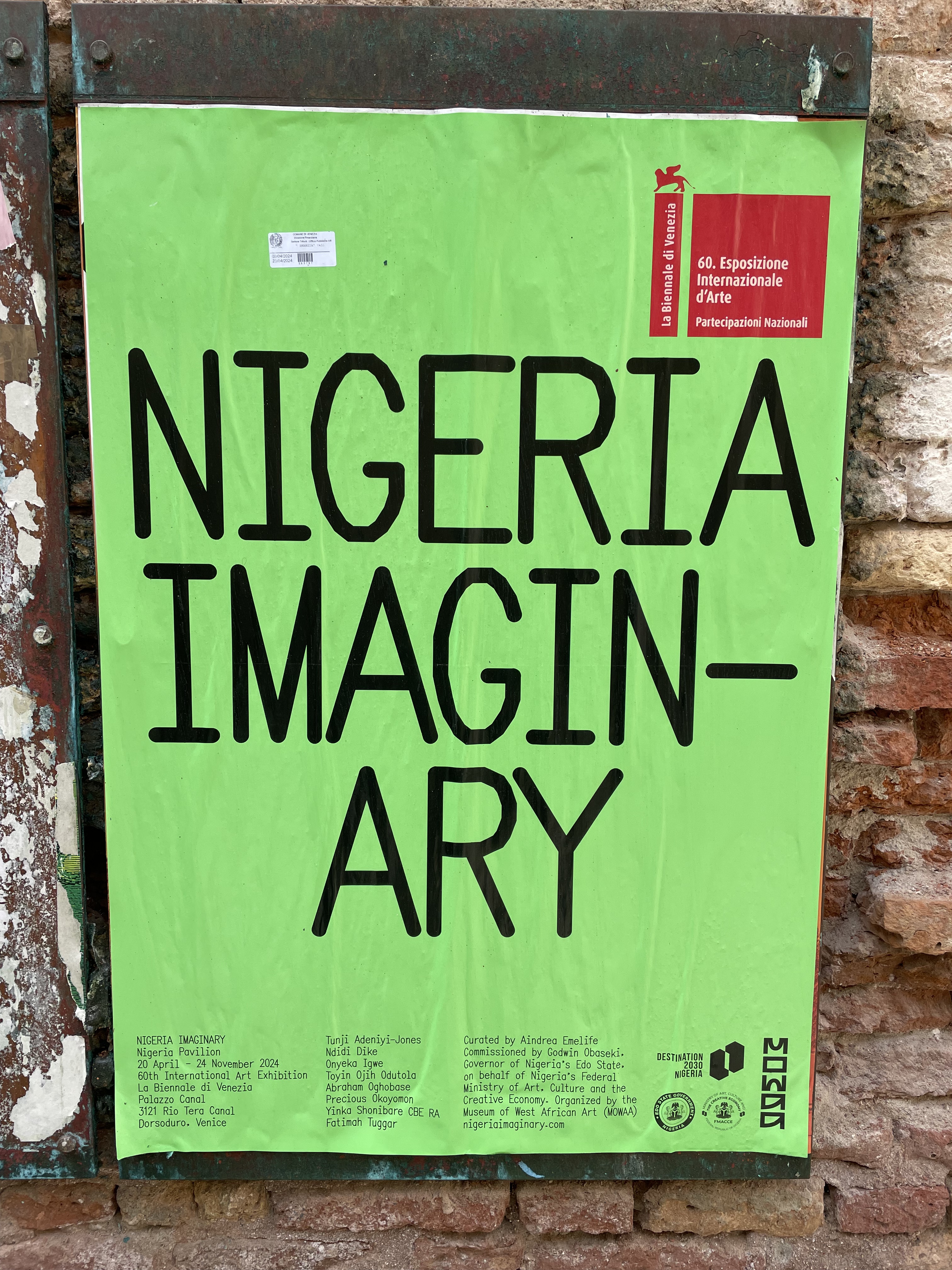

The Benin pavilion is part of the Arsenale section of the Biennale, along with quite a few other national pavilions. And the Nigerian pavilion, called “Nigeria Imaginary”, is one of a few national pavilions that are sprinkled here and there in Venice outside the main Biennale areas Giardini and Arsenale. It was fun to come across these as we wandered around Venice.

So, getting started in the Giardini, the Canadian pavilion is relatively new (1957) and beautiful:

This pavilion is also unique in that a large tree is growing out of the middle of it, and seems to fit beautifully. You can see it at far left in the above photo.

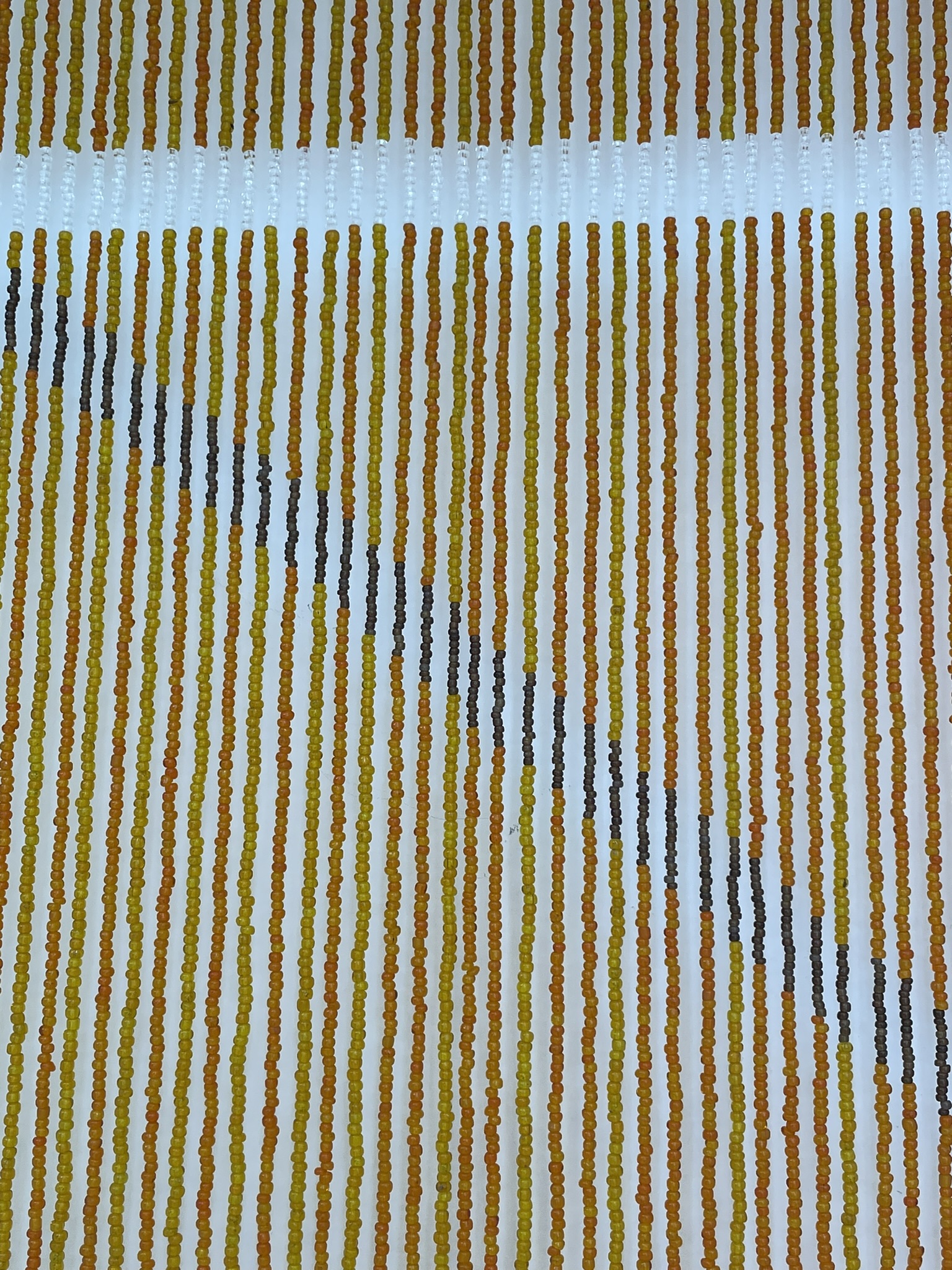

The Canada pavilion is hosting a single work, “Trinket“, by the Franco-Canadian artist Kapwani Kiwanga, based in Paris. The work is mainly composed of voluminous strings of seed beads, many of which historically came from Murano, one of the Venetian islands, and were used as currency in many cultures including North America. There’s also an interesting YouTube video about the exhibit.

A question that occurs to me about this work: Why is it called “Trinket” rather than “Seed Beads”? The Biennale page about the work puts it in an interesting historical context from the standpoint of seed beads, but doesn’t mention anything about trinkets.

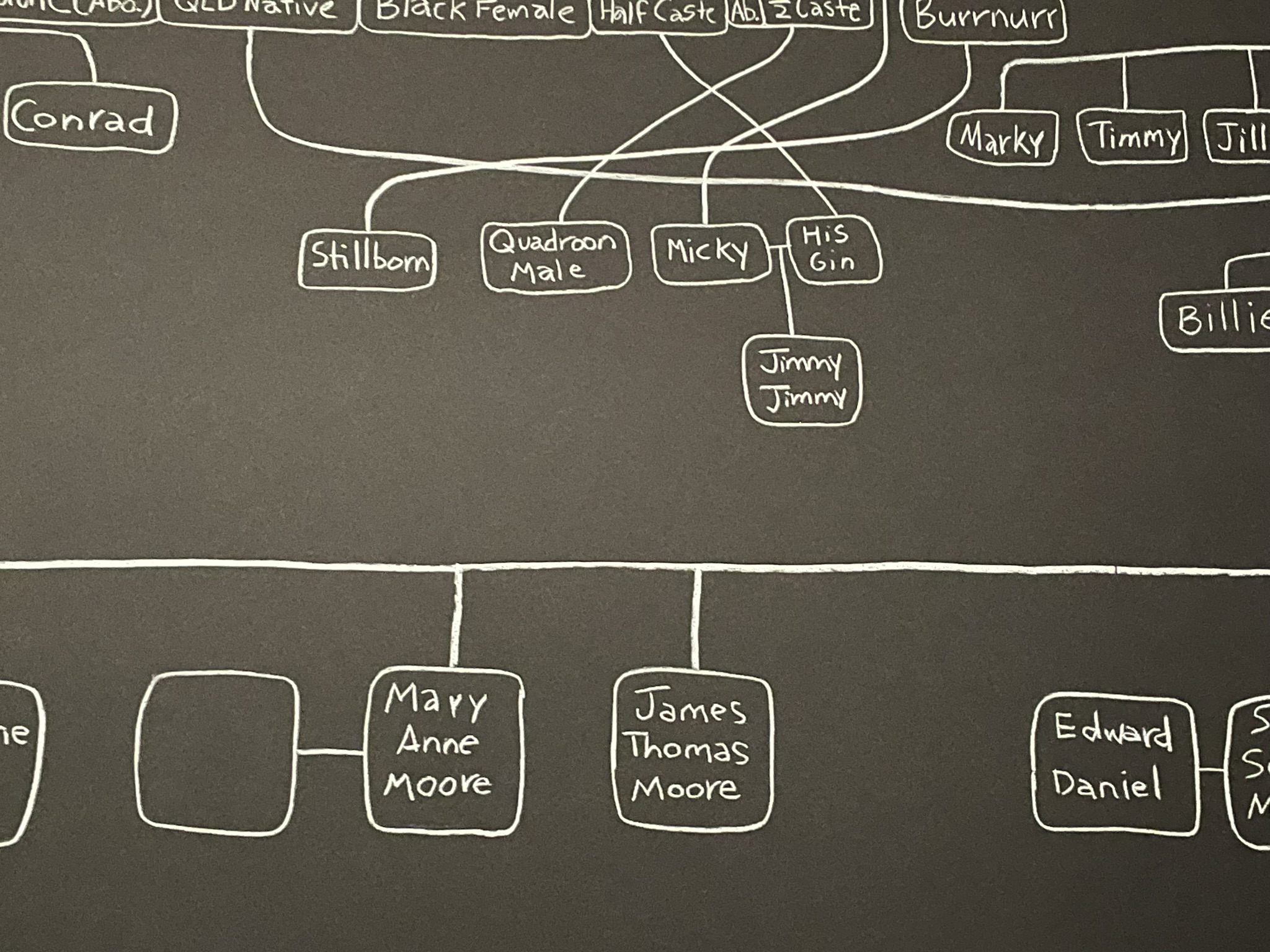

The Australian pavilion is also in the Giardini, very close to the Canadian pavilion, and is one of the newest pavilions, having been built in 1988. It also contains a single work, First Nations artist Archie Moore’s “kith and kin”, which was created specifically for the pavilion.

Moore’s work was awarded the “Golden Lion for Best National Participation” in this edition of the Art Biennale and represents the first time an Australian artist has received this award.

An article in Art Review describes it well:

For “kith and kin”, Moore has installed a reflective pool in the center of the Australia Pavilion that pays tribute to the injustices faced by First Nations peoples today. Set on a platform above the pool are 500 document stacks mainly consisting of partly redacted coronial inquests into the deaths of Indigenous Australians in police custody dated in our lifetime. Across the walls and ceilings of the space, a celestial, genealogical chart spanning 65,000 years reminds visitors that ‘the reports do not represent nameless statistics; rather, they are children, siblings, cousins, parents, uncles, aunts, grandparents and great-grandparents’. A convergence of the personal with the political, “kith and kin” also highlights similar injustices around the world. The exhibition is curated by Ellie Buttrose and commissioned by Creative Australia.

The final Giardini pavilion I want to highlight was one of my favorites, the City of Venice pavilion. I actually liked it quite a bit more than the Italian pavilion, which was in the Arsenale and, admittedly, much more boundary-pushing and avant-garde than the Venice pavilion.

Several artists were featured in the Venice pavilion but I want to focus on just two, both of which I found to be very impressive, in different ways.

First is Pietro Ruffo, who created the highly elaborate, large and very detailed works shown below, part of a work called Image of the World (“immagine del mondo”). Fortunately I found an English language description of the work on the artist’s website. To summarize, the website states that this work refers to the human need to tame nature through study. It was inspired by the Marciana Library in Venice, one of the earliest surviving public libraries, which holds one of the world’s most significant collections of classical texts. The work’s three components are:

- bookshelves containing scrolls depicting the leaves and branches of a primeval forest

- the Constellation Globe (seen below), depicting the ancient view of what existed outside the earth

- the Migration Globe, depicting the migration flows and “cultural contamination” (a reference to the Biennale’s theme of “Foreigners Everywhere”) that has created the earth as we know it today

Here’s a video showing the rest of the work including the “Migration Globe”.

The thoughts behind Ruffo’s work are perhaps a bit lofty and “in the clouds” for other humans to fully understand, but his execution and creativity are, to me at least, impeccable.

The second artist that caught my attention in the Venice pavilion was Safet Zec, whose work certainly brings us crashing back down to earth, but also with great beauty. Zec is one of the oldest and most celebrated artists in the Biennale. He’s now 80, grew up in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and has had over 70 solo exhibitions around the world. This New York Times article from 2010 provides valuable background.

Zec is considered a “poetic realist”. He came of age when abstraction was the fashion in visual art, so it has taken decades for his more traditional, figurative approach (though clearly with rough, contemporary stylistic influences) to be noticed and appreciated. His works have great power and as you can see below, have additional impact due to their often very large size. One of his several homes is in Venice and this must be why he was included as part of the Venice pavilion.

To give an idea of how it feels to walk around the pavilions in the Giardini, here’s a video I created showing a canal (rio) in the middle, with the Australian pavilion on the right and another area across a bridge on the left containing the pavilions of Serbia, Austria, Egypt, Poland, Romania, the city of Venice, Brazil and Greece.

The amazing paintings below are part of the Benin pavilion, which is for the first time part of the Biennale, housed in one of the Arsenale buildings. The artist is Moufouli Bello, a Beninoise painter known for “large-scale portraits of women with bright blue backgrounds and luminous colors”. She was profiled in this CNN report.

Though the photo and video above feature Bello, there was more to the Benin pavilion. It has become a favorite of visitors and has been written about in multiple publications, including in the “10 Must-See National Pavilions” published by Art and Object magazine.

Finally I need to describe the Nigeria pavilion, located outside the Giardini in the Dorsoduro district (sestiere as they call neighborhoods in Venice), near the Grand Canal, Ca’ Foscari University and Accademia Museum. It’s a group exhibition in the semi-restored Palazzo Canal.

According to the New York Times, this pavilion has proven to be very popular with visitors and we really enjoyed it too. Each artist has a room and there’s a lot of variety, all the way from heavy political commentary to echoes of the ceiling paintings of the Italian Renaissance.

Below is Yinka Shonibare’s Monument to the Restitution of the Mind and Soul, which “replicates 153 objects looted from Benin City in 1897 by British forces, amongst them a bust of Sir Harry Rawson, a British naval officer who led the punitive expedition, painted in Batik style pattern.” These objects are traditionally referred to as the Benin Bronzes, but apparently they were not all bronze.

Another useful article about the Nigerian pavilion can be found here.

A more sensuous and pleasant example of what can be found in the pavilion is the painting Celestial Gathering by Tunji Adeniyi-Jones. It’s shown below and can be found suspended from the ceiling of one of the rooms in the palazzo. It was inspired by Renaissance ceiling paintings, among other things described very well by the artist in this YouTube video. The video is worth watching for the artist’s deep, sonorous voice alone!

That’s all for Part 1 of my report on the Venice Biennale!

Stay tuned for Part 2 in the next few weeks, in which I’ll provide highlights of the International Exhibition in the Arsenale and will show some favorites from the many “collateral” exhibits that are currently found all around Venice.

Leave a comment